A friend recently requested an analysis on the exterior ballistics of projectile weapons in the context of an O’Neil cylinder, a proposed type of mega-structure space station for the long term habitation of human in space, where the cylinders are spun such that the centrifugal inertial “force” simulates the effect of gravity.

The exterior ballistics problem in the context of an O’Neil cylinder is an interesting one. The most significant difference with that of conventional exterior ballistics is that the force of gravity, proportional to the inverse-square of distance between center of masses and towards the center of Earth, is replaced by the inertial effect of rotation, proportional to the distance to the axis of rotation, and acting radially outward from the center of the O’Neil cylinder. Therefore, trajectories on O’Neil cylinders bends radially outwards, just as trajectories on Earth bends radially inwards. As the horizons are flipped, in either case the observer of an artillery shell will notice it falling towards the local horizon.

Since the O’Neil cylinder remains hypothetical as of writing (2025), I was unable to find academic resources discussing the particular details of the internal atmosphere, especially in regard to the potential differentiation into layers, as is the case on Earth. Therefore, a simplified, isothermal model is used, with the temperature assumed constant everywhere. The atmosphere is assumed to be in hydrostatic equilibrium, with the pressure decreasing in proportion to height and local acceleration. The standard ballistic condition (101.325kPa, 289.1K) is also assumed at the inner surface of the rim.

The Coriolis force is another effect (alongside centrifugal and Euler force) that must be accounted for when using an rotational frame of reference. It has the expression , and this acceleration can have an effect on par, or exceed the centrifugal acceleration ,

.

What all of these means is that, mathematically, if we extend the definition of height-above-ground into the negatives, extend the elevation to include the third and fourth quadrant, substitute the correct equation for local acceleration and atmospheric conditions, and add a term for Coriolis force, the exterior ballistics of a projectile in an O’Neil cylinder can be described with a modification of the conventional formulation. This enables me to reuse most of the code base I have written for the calculation of range tables on Earth to that of an O’Neil cylinder with expediency.

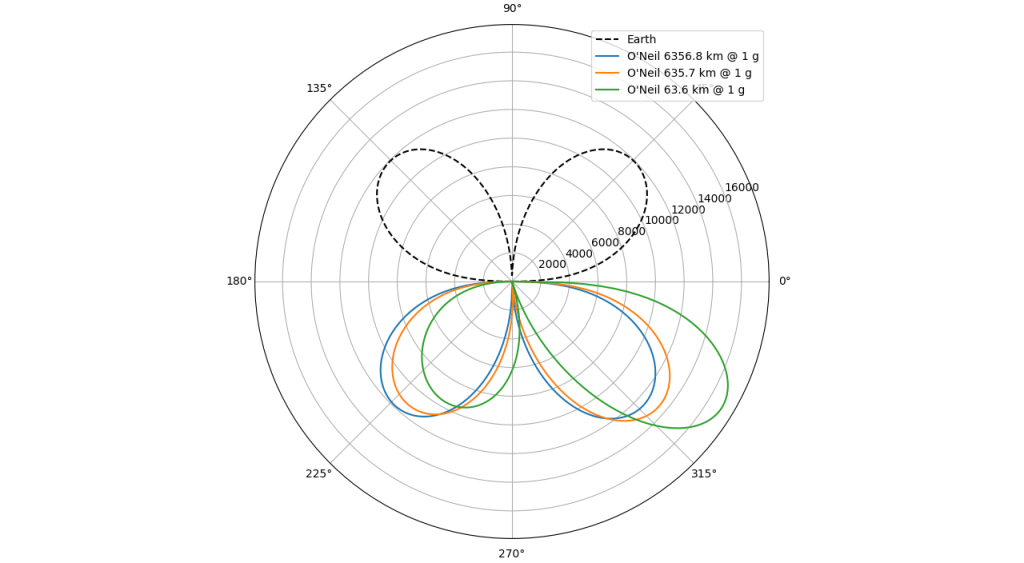

The first series of calculation was conducted to establish the influence of O’Neil cylinder’s radius on the trajectory of howitzers. The artillery piece used for this is the M-30 howitzer, firing the OF-462 projectile at a muzzle velocity of 515 m/s. Trajectories for O’Neil cylinders with radius of 1, 0.1, and 0.01 Earth radius are calculated. The range achieved by trajectories at elevation from is plotted on a polar plot. The station is assumed to be rotating counterclockwise in this view, such that the 3rd quadrant is the “pro-spin” and the 4th quadrant is the “anti-spin” direction. The terrestrial range is plotted in the 1st and 2nd quadrant for reference.

The result shows that for O’Neil cylinders, the effect of a linear decrease in gravity and atmospheric density has the effect of increased the range of artillery weapons on an O’Neil cylinder as compared to on Earth in all cases, although this is overshadowed by the effect of Coriolis force, which has an asymmetrical effect on the trajectory, depending on the direction of firing: when shot in the spin-direction, the optimal elevation to achieve maximum range is increased, while the maximum range that can be achieved is decreased. The effects are reversed for the reverse direction.

This may be further explored in the projectile-intrinsic reference frame, with the horizontal axis aligned with the local horizon, and the vertical axis radially inwards towards the axis of rotation. This makes it apparent the effect of Coriolis force as it acts to distort the trajectory towards the anti-spin direction.

If we were to ignore the Coriolis effect for a moment, the condition for projectiles to overcome and reach the axis of rotation, or shooting “antipodal”, for a lack of a better term, can be expressed analytically for airless bodies: Let the radius of the O’Neil cylinder be and the acceleration along the rim at

, then the magnitude of the acceleration anywhere that is

from the axis of rotation is:

This is a consequence of the centrifugal acceleration scaling with , as

if the angular velocity of rotation is expressed as

. This can be integrated to yield the work that is done by the centrifugal force as it moves a test mass

from the axis towards the rim:

The kinetic energy of a projectile is , and equating the two yields the “anti-podal” velocity as:

Interestingly enough, this is also equivalent to the velocity at which the rim moves in relation to the axis of rotation. This can be explained if we consider that another way to move from the axis to the rim is to free-float along the radius of the cylinder, and then once at the rim, accelerate to match the rim’s velocity in the extrinsic reference frame. A useful way to think about this result to consider the test mass and the cylinder as a system, wherein so long as energy is not dissipated (by drag or friction), the system is conservative and the work done going from any two points within it is independent of the path that is undertaken.

However, as have been established previously, the Coriolis force has the effect such that all antipodal trajectories bends around the spin axis. This, and that aerodynamic drag being dissipative, prevents this velocity from being sufficient. For example, substituting the 515 m/s figure we have used back, in an airless body, this should be sufficient to conduct anti-podal firing missions for cylinders smaller than 27 kilometers, but in practice, numerical calculation has shown with drag, this is reduced to between 10 and 15 km. An interesting analogy would be to compare this with the “orbital velocity” calculated for a body at surface level, versus the actual required delta-V (change in velocity) expended to reach said orbit.

The Z-axis

So far, we have discussed the exterior ballistics as a 2-dimensional problem, which is a reasonably accurate approach on Earth. However, O’Neil cylinders differs from a sphere by having only one axis of symmetry. Fortunately, as this axis is parallel to the axis of rotation, projectile’s velocity component in this plane should not result in additional Coriolis force effects1. Unfortunately, the effect of drag cannot be decomposed as simply. Due to time and modeling constraint, this avenue is not explored further in this article.

Some Implication for Ballistics Weaponry in the Interior of an O’Neil Cylinder

The same friend that approached me about this problem is world-building a sci-fi setting in the context of sentient being developing on pre-existing O’Neil cylinders constructed by precursor species, with a specification of 500km radius, generating 1g at the rim.

As mentioned previously, this implies an anti-podal velocity of around 2214 m/s. Accounting for atmospheric drag, this puts the muzzle velocity required to achieve antipodal firing at 4-5 km/s for tubed artillery, which is on the high end of the attested performance for these systems. On the other hand, a similar system, on Earth, would only be capable of achieving a range perhaps only 400 km, while in the case of the O’Neil cylinder it handedly reaches near 1600 km (in ground range).

Further, this level of performance is well within the realm of missile weapons. The velocity calculated for gun-launch should represent a worst case scenario for missile type weapons, which experience less drag loss, as they accelerate to their burnout velocity only when out of the densest part of the atmosphere. Taking a rough estimate, this corresponds to a high-end tactical ballistic missile with an equivalent range on Earth of 500 km as the lower bound, to a high end MRBM with a range of 3000 km as the upper bound.

The takeaway here is that, ballistics weaponry, especially as they approach the spin-velocity of the cylinder, gains significant range advantage when compared to their terrestrial counterparts. Given this level of performance is readily achievable technologically, this has immense implication on both a tactical and a strategic level, especially in a nuclear environment, although the precise details must by necessity be analyzed on a case by case basis.

- as the result of cross product distributing over addition. ↩︎

Leave a comment